Why I Write

On our summer porch at night, the fireflies hustling about in the near fields, my grandfather Johnny Igoe read W.B.Yeats to me when I was a youngster, rocking in his chair, smoking his pipe, making music and rhythm in his life, and in mine. I was, at the first of Yeats, about six years old.

"Listen," he'd say, pointing his finger up. "Hear the music. Know the sound. Feel the grab."

Johnny Igoe, spellbinder remembered.

On that porch on Main Street, a mere mile out of Saugus Center, he (and Yeats) holding forth, his voice would roll into the field where fireflies lived. His words would mix with the fireflies waiting on my bottle capture or a sense of deeper darkness where they could further show off their electric prowess. The times were magnetic, electric. I knew what attention was.

Oh, I loved those compelling nights filled with Horseman, ride by; Prayer for My Daughter or old marble heads, captivating me with a sound so Irish I was proud. I will arise now and go to Innisfree/ oh, and the deep heart's core. The lineage found me: I didn't find it, and the echoes of those nights ring yet.

But other things came repeatedly for him and still come: Johnny Igoe only ate oatmeal in the morning, a boiled potato and a shot of whiskey for lunch. He made Yeats's voice to be his own, that marvelous treble and clutter of breath buried in it, The Lake Isle of Innisfree popping free like electricity or the very linnets themselves, Maude like some creature I'd surely come to know in my own time. Johnny Igoe wrote his poems, and also yielded me Mulrooney and Padraic Gibbons out of the long rope of his memory, the knots untied all those Saturday evening of his life and mine, on that porch. He launched many of my own poems here, by the dozens, and at the end, at 97, stained, shaking, beard gone to a lengthy hoarfrost, potato drivel not quite lost in it, he gave me his voice and eyes alive to this day, sounding out in his own way.

Later, time hustling me on, in a Caedmon Golden Treasury of Poetry record I heard Yeats read his own material, three short poems, and swore it was Spellbinder Johnny Igoe still at work. I have not forgotten a word or an echo of all that.

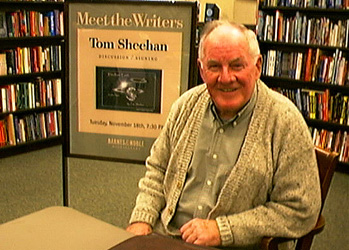

"A Collection of Friends," memoirs, has been published by Pocol Press, and a poetry chapbook, "The Westering," by Wind River Press. His fourth poetry book, "This Rare Earth & Other Flights," was issued in 2003, by Lit Pot Press. He has five Pushcart nominations, and a Silver Rose Award from American Renaissance for the Twenty-first Century (ART) for short story excellence.

Arrangement by Tones

Silence is

the color in

a blind man's eye,

his red octaves

screaming two shades

of peace in sanguine vibrato,

a purple strike

lamenting rivers

and roads lashed in his mind,

like a crow's

endless caw-ing

of blackness anticipates nothing.

And now,

for all my listening,

it is your hand on my heart,

the mute fingers

letting out the slack

where your mouth reached,

your moving away,

a pale green evening

down the memory of a pasture.

Beneath Vines and Peach Tree

A Neighbor's Ashes

(for Herb Wills)

Vinegar Hill,

Sleepy, boot-brown

From the long heat,

Ready to firecracker,

Suddenly bustles

Like a tarpaulin

Catching a first breeze

Sweet as sherbet.

One ripple,

Air fueled, folded long

As a wave, starts its

Dance off the summit

And races shoreward.

Wind water,

Thick as suds, airy,

I swear some Atlantic green

In it, touches my feet.

You still ache

In ashes

The grapes fall on,

And the now-scented loam

Where taupe pits

Go down with ants

Into never before

Hollows.

Your sweat is a yeast

In the compost pile.

I watch where you

Stretch your gardens

Into the river, the long reach

Of your spade.

Burial for Seamen

Tonight I think of

Jonathan Diggs and how

he salts the Atlantic,

how the horse of his voice

shakes the water from the under-

neath, cracks the rocks

the small fist of Nahant

left-jabs in the ocean.

The dory

came riding in high and free

as a cracker box, the oars gone,

locks ripped away as if he had

broken all his muscles on them,

the anchor gone as Davy's gift,

not even a handful of line

left in the loop.

One incon-

spicuous mark gathered in the final

counting: JD9. It was Jonathan's

ninth boat, and the first to outlive him,

the first to come back without that

oarsman.

Seventy-year

old men do not swim all night, do not

ride on top like debris caught on the

incoming tide, do not materialize on-

shore once they are that wet.

They go down

like Jonathan Diggs, shaking their fists

at the Atlantic, shouting the final obscenity

they have waited all this time to use, know-

ing the exact moment to employ it. They send

a sound running along water lines, burst it

into sea shells

Sing it as

a tone of surf busting all September nights

when ocean listeners count for sailors.

They become the watery magnet pulling

men from inland fields, in turn are

magnetized by moon's deep clutch

on the rich pastures of the sea,

and sleep then

only in tight caves, soundless and dark

in their wearing away.

Evening, by Hawk

World-viewed incandescence; sun up

under his wings with last quick volley,

slipping through a hole in the sky, lilting

the soon-gray aura without a sound,

an evening hawk appears above us.

From Yesterday he comes, from Far

Mountains only Time lets go of. Under

wings steady as scissors a thermal

gathers, not sure the joy is ours,

or his. It flings him a David-stone

racing the Time-catch at heart,

at our throats. There is so much

light falling down from him,

from wing capture, we feel

prostrate. To look in his eye

would bring back volcano, fire

in the sky, a view of the Earth

Earth has not seen yet. In apt

darkness chasing him, in the

mountains where gorge

and river give up daylight

with deep regret, his shadow

hangs itself forever, the evening

hawk sliding mute as a mountain

climber at his work,

leaving in our path the next

hiker's quick silence, stunned breath,

the look upward on a frozen

eye and a driftless wing

caught forever.

Hermit Island, Maine

I walked

in the syrup of night

down a Hermit Island road

between snoring and 3 A.M. loving

waiting for the fish to wake.

I felt

the grace of stars

and the abrasives of sand,

the mad interplay of elements

thrusting at moccasins and eyes.

Ahead

the moon pushed

a broad blade of light

down through the perfection

of trees, a leaf scattered the delight,

a moth struggled toward the infinities.

I drank

my beer, remembering

a star fish caught hours before

on a burst of rocks, its five fingers

searching as my senses for momentary salvation.

I realized

I had no enemies,

I had no hate. I moved

out, into, and was alone

with the grace of stars

and the abrasives of sand.

Letter to the Author: tomfsheehan@comcast.net