Have you experienced the shortfalls of conventional western medicine? The in-and-out processing? Fast scalpel exploration? Felt less like a human being and more like a mechanical process in need of "oil and lube?"

What kind of a doctor would you like to have as a family physician? Wait a minute. Are there such things as family physicians? You know, the ones who not only get to know you but learn about your family circle, as well, and its impact upon you.

Have you been searching for a medical practitioner who combines the training of western medicine and the knowledge of alternative medicines? Are there any?

There is at least one, Lewis Mehl-Madrona, and he is bent on changing medical school education so that there are more. Coyote Medicine is his story, his autobiography of how he, Cherokee, Lakota and white, went to Stanford Medical School in the mid-1970s and subsequently struggled with western medical practices and politics as he tried to bring his vision of wholistic health care to reality.

An extremely bright youngster, one could consider him fortunate to have had the broad influences that he experienced. His family for the first five years of his life contained his great-grandmother, a Cherokee healer. He describes her death in that she announced to her daughter (his grandmother) and his mother that that night she would die (even though she was quite hale and not sick). He writes that he watched her comb her long, gray hair ("like one of the mohair afghans she used to crochet"), sing her death song, pray, and ask the Great Spirit to take her. And Great Spirit did that night.

His grandmother was also Cherokee, and his step-grandfather, her husband Archie, was Cherokee-white ("half-breed" as Mehl-Madrona calls him and himself). Archie was his source of many things good and strong, in one case, putting a stop to his nightly belt-whippings by his step-father. Archie's spirit would appear in sweat lodge ceremonies that he experienced in later years, even when Archie was still living.

His mother was Cherokee-white, and Mehl-Madrona lauds her capability in graduating from college and working to give him the opportunities that he had. I mentioned that he was smart. In working for an Eagle Scout badge in physics at 13, he ended up assisting a college professor in his experiments on splashes and discovered a love for the feel of campuses. When his mother was unable to give him a ride one weekend, he discovered hitchhiking. I can imagine that she must have gone nuts sometimes, wondering where on earth he'd gone off to. He describes hitching from Ohio to Boston to visit Harvard. No small distance. Understandably this was the '60s, and you could get a long ways with your thumb without a lot of the worry that has attended hitchhiking for the past two decades.

He also took community college courses at 14, graduated from high school "before turning sixteen," studied at Indiana University taking medical and grad schools courses, got admitted to Stanford Medical School at 18, and graduated at 21. But what else would you expect from a person who read Kierkegaard and Tillich at age 12 and gives them credit for teaching him about faith?

It was on his second rotation in medical school, urology, that he met four men all in renal failure at the same time. Three were beyond hope; one was looking at a kidney transplant. All had been active, healthy men until a standard physical exam found protein in their urine. All had undergone renal biopsies, gotten infected, and then their kidneys had shut down. As a fellow student from Saudi Arabia noted, they "had the 'advantage' of the best preventive health care in the world." Perhaps if Mehl-Madrona had come across them individually over a period of several months, it would not have had such impact. This also seemed to be the first time that he experienced the playing of the politics of medicine, which caused him to think long and hard about what it meant to heal a person.

"I was surprised to find, in medical school, that few shared the awareness and acceptance of healing I had known in Kentucky....I took it for granted that there was a spiritual component to illness, and wellness, too, and that doctors would respect it...It wasn't until I experienced the shock of seeing four devastated but previously healthy men together in the same renal room that I began to think the healing traditions of my childhood might have something to offer the professors of Stanford....I was too naive to recognize that even the idea of healing-without drugs, surgery, or other invasive care-was considered 'class' and counter to the conventions of medical schools."Stanford in the early '70s actively recruited minority students, and Mehl-Madrona was one of nine Native Americans in the med school, who supported each other in getting along in a system at odds with their cultural values and behavioral habits. One of them introduced him to a sweat lodge and healing ceremony in Wyoming, his first ever. Having been brought up in a Christian tradition, overlain with his grandparents' Cherokee beliefs, a part of what he experienced came out of that:

"In an ecstasy born of the drumming, I heard wordless mysteries, felt the boundless love of the Christ spirit, caught a glimpse of the compassion of the angels... I saw him standing beside the White Buffalo Woman, son and daughter aspects of the Creator."It is there that the medicine man tells him to remember to honor Coyote, and Archie, his grandfather. "Coyote does exactly what he was created to do. He is faithful that way. You must be, too." After that experience, he knew that he would not accept the view "that people are only the incidental occupants of a set of organs," that he would "avoid the seduction of success in conventional medicine, and to continue to strive for a vision of what real healing could be."

It took many trials to get there, including a dispassionate marriage, a divorce, failed residencies, a clinic that went bankrupt, poor choices in relationships, and the effort it took to maintain relationships with his children, post-divorce. But among the trials were the pleasures of receiving teachings from Native American healers, participating in and eventually leading ceremony, and ultimately melding his two heritages in his practice of medicine.

I experienced a sense of connection with Mehl-Madrona as I read of his trip to a conference in Burlington, Vermont, and his going to the Sun-Ray Center in nearby Bristol. Having lived some 28 years in Vermont, it's always exciting when a story I'm reading moves into the state, however briefly.

It was at the conference that he met the woman, a midwife, who became his second wife. But there is more of a connection than that. The midwife had helped her sister birth her baby, and the sister has gotten sick and died soon after the birth. As I was reading this, a little shiver went up my spine because I knew a woman in Montpelier who died just as he described, at about the same time period. Indeed, we other women in the community had difficulty understanding how she could die so quickly when the delivery had been fine and everything seemingly okay. I remembered thinking that she shouldn't have been left unattended at home the day after the birth. Now, upon reading his description of toxic shock syndrome caused by a virulent strain of strep bacteria and that it can kill a woman in 90 minutes on an emergency table in a hospital, I can understand. He footnotes this in particular, and I repeat it here just to spread the word a little further:

"Strep bacteria are often carried in the sore throats of a new mother's sex partner. Near the time of the delivery, during the winter-spring sore throat season, care should be taken to avoid oral sex. During that season 20 percent of people test positive for strep throat, and though a virulent strain such as M-1 among those 20 percent of case will be rare, it may prove to be deadly for the mother."He ultimately finished his last required residencies at the University of Vermont's Medical Center after his marriage, nearly twenty years after graduating from medical school. What knowledge he gathered along the way, though!

He includes a number of fascinating client stories, illuminating both the positive outcomes and the effects of negativity on outcomes, pointing out that it is his experience that with serious illness, no matter what the treatment, 20 percent will "thrive over the long term." It has been his observation that 75 percent will improve for a while and then deteriorate.

He believes that the key to the "thrivers" is trust, an "implicit, deep faith that leaves no room for doubt or skepticism." Such a person doesn't say "I believe this will work," (and here is an good example of the difference between faith and belief) they will say and know within their whole being, "I know this will work." I know that if you haven't personally experienced such complete faith, it is hard to imagine being able to do that. The slightest skepticism would be the chink in its armor. But he goes on to say that the power of "ritual prayer, song, and dance allows us to forget our skeptical world view for a moment." It is in the performance of ritual ceremony that brings in the earth's energy and power and creates harmony between ourselves and the earth and within ourselves, harmony that "is the music of healing."

Several Coyote stories are retold in this book as Mehl-Madrona moves through the integration of the qualities of Coyote into his practice of western medicine and whole-being medicine. He ruminates about Coyote and his identification with it.

"For the powers of coyote medicine to win popularity in the mainstream, its practitioners will also need to be survivors, tricksters, and clowns. Clowns, to disarm any establishment foes, and charm them into paying unexpected therapies serious attention. Tricksters, to have their wits about them, to thrive in a hostile environment. And survivors, to persist even when success seems unlikely and the path obscure."The last couple of years I've found myself drawn to pow-wows, to books on Native American cultures and traditions, and yet I've strongly felt that I am the outsider, the Anglo, because I cannot lay claim to any Native blood in my ancestry. I've read articles by people who want to keep tribal ceremonies free from white participation and articles by people who share ceremonies with non-Natives. At the very end of his book, Mehl-Madrona writes that

"I believe Native American spirituality is a gift to us from North America herself. It is the natural spiritual path for those who live on this continent. Native American people have been the preservers of this spiritual path for centuries, but they do not own it. No one can own a spiritual path."I'm sure there are some who would disagree. But I don't think the medicine man at his first sweat lodge and healing ceremony in Wyoming would. After all, one of the participants was the local Roman Catholic priest who believed that the outlawing of Native American religious ceremonies was wrong and who attended partly in case the local law enforcers showed up.

There was just one wrong note in the book, and that was "Frank Deere green," referring to the color of a tractor. Since I grew up with tractors that were that particular shade of green (and there is only one), I know that there is no "Frank Deere green." The only reason I could figure for the name change had to do with the fact that the true name is a trademark.

In mid-December I picked up a magazine called Spectrum: The Wholistic News Magazine because its banner read "Spirit Medicine: Lessons for Modern Doctors From the Native American Tradition." The article was an interview with Dr. Mehl-Madrona, who is now Medical Director of the Center for Complementary Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and a research assistant professor in the Native American Research and Training Center at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson.

His message remains to not give up; when it comes to healing, try everything there is available. And my message is, is that if you're fortunate, you'll come across one who practices whole medicine, who listens and learns of you, and from that creates a healing path.

May you be so blessed should you have need.

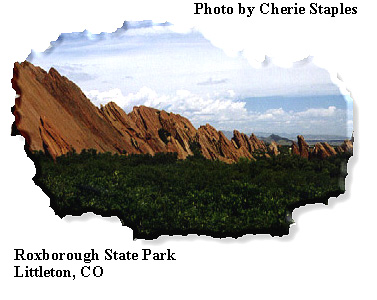

Cherie Staples

Skyearth1@aol.com