I didn't hear those words quoted at the "Good in Nature and Humanity Conference" early in May, but I didn't hear everything that was said, either. This morning (the Sunday that I finish the June issue and write my column) they rose in my mind as I lay in bed after waking. I'm sure they came because I have been contemplating the subject of this month's Skyearth Letters ever since I got home from the conference.

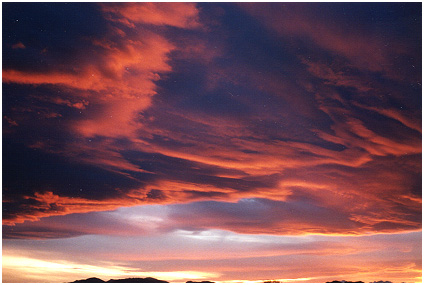

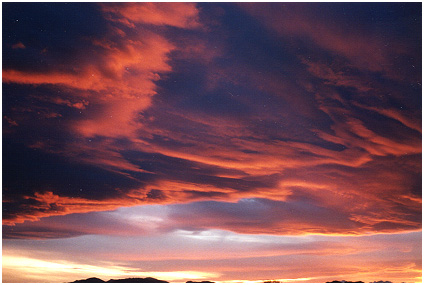

That particular verse is often quoted. Sometimes the words are affixed to gorgeous mountain-and-sky pictures, usually with the sun partially obscured by clouds, creating that effect known variously as "the-sun-drawing-water" and "God-beams." The particular confluence of verse and scene has perhaps become a part of Western consciousness.

Why is it that so many of us are drawn to those places that rise high along the horizon? Why do I personally have the strong need to see a goodly mountain in my local viewscape? In Vermont, it was Spruce Mountain that fitted in the aisle from my back door through the trees. In Colorado, it is the combination of foothills and fourteeners that serrate the western horizon seen through the front window.

Many of us experience that deep-felt need to connect to the living, and non-human, earth. For a woman in Brooklyn, all it could be was growing flowers in pots on the windowsill. For others, it is a nearby municipal park with trees, grass, wildflowers (hopefully) and water. As we move further out, for some, it may be just their backyard, even though they poison it with weedkiller. Streambanks, mud ponds, woods (particularly fine, old trees), grasslands left to run wild, desert-scapes of cacti, the swells of sand dunes, and, always, the mountain peaks and ridges, all reflect inside the observer in an indescribable way to create a joyous feeling, a feeling that is so heart-felt that words fall away.

The people at the conference were sharing that feeling of heart-felt joy through their personal stories of how the landscape has shaped their spirit. Bob Pershel of The Wilderness Society' Network of Wildlands Program, told the story of working as a forester and training new forestry graduates in woods-work. One time he and one of these fellows were cruising a woodlot, marking timber for cutting. Bob described his moving through the woods as a slow, considered perambulation, where each tree was weighed figuratively on the scales of the universe before a mark would or would not be placed upon it. Working back and forth along his swathe of trees, he would catch glimpses of the newly-minted forester surging far ahead on his particular swathe, his actions clearly denoting a lack of feeling for the trees themselves.

Bob had the huge room of listeners holding their breaths as he told how the next time he and the other fellow met on the edges of their swathes, Bob confronted him and literally pushed him up against a big tree, holding his head to its trunk. He didn't see him again until he was done his swathe, when he caught a glimpse back through the trees of the man reaching out and slowly touching a tree. Bob did not stay to see whether the tree got marked or not. That wasn't the issue; the issue was engendering love for the creation that one had an affinity for, the creation over which, in this instance, one had the power of life and death.

I wrote down this phrase from Bob's talk: "tying our work to our guts, and understanding who you are inside nature." And he asked, when did work stop becoming worship? I am reminded of the artisans who created the tremendous Gothic cathedrals, surely one epitome of work equaling worship.

Wendell Berry lives the "work=worship" life. I heard Wendell as the keynote speaker on one evening and the following day as one of a panel of agriculturalists, working around the topic of "Linking Spiritual and Scientific Perspectives with an Environmental Ethic." Wendell is a writer of short stories based in his native Kentucky region, poetry, and essays and books on the state of the land and its use, ecologically and economically. He's also a college professor and a farmer of his family's land. He does not believe in the "bigger is better" economic paradigm.

No one on the panel had good words to say about the state of agriculture in the United States and, because of the globalization of industrial agriculture, around the world. Yale professor John Wargo noted that there have been 250 billion pounds of pesticides/herbicides sprayed since 1900 and I would say that most of it has been since World War II. With 75,000 different 'cides being used, we are all the guinea pigs of their science. None are tested well, and most not at all. [And yet the American Cancer Society still is after a "cure" for cancer, when the best and healthiest cure of all is prevention by eliminating our poisoned environment, but that notion doesn't fly in the economic nightmare we've created in the agricultural and industrial economy.]

Someone commented that our educational system is training children to believe that organic sustainability is wrong and corporate agriculture is right. When panel members were asked what should we, the listeners, do, the answer fired back was to buy and eat/use organic. Put your money where your mouth is by supporting organic, soil-sustaining agriculture, and first in line ought to be the educational institutions, such as Yale University where we were meeting. An audience member added that, along with serving organic food, the universities ought to be serving and teaching organic thinking.

We were reminded by Wendell that the renewable economy, operating out there on the fringes of the mainstream, is not subsidized, whereas the extractive economy is heavily subsidized. [If the true cost of making and disposing of a product were part of its selling price, we would have been renewable long ago.]

Finally, in the spirit of environment, one farmer told how she "grew up in the crick." The freedom to explore the natural places alongside and in running water, as the creek worked its way across her parents' farm, blossomed into deep caring for the natural world and for the world of planting and harvesting crops in a resource-conserving manner. Others echoed that sentiment. An Amish farmer described his experience of working out on the land as living a prayer.

I'll leave you with that thought: whenever we are out on the land, deeply experiencing nature, we are living a prayer, a communion with …however you choose to contemplate the life force of this Universe.

Cherie