WITHIN THE CHILD

We've been bombarded this past spring with a myriad of horrible experiences, tragedies with school children. With much consternation, people have wondered how these children, the shooters, grew up to have the thought that it was okay to take guns to school with the avowed intent to kill their peers and whoever else happened to be standing around. Even with parents who truly seemed to care about their child (the Oregon boy), there still seemed to be no lessening of the dark mind within. (It's interesting to note that the Humane Society sees a direct link between hurting and killing small animals for fun and the move to hurting and killing bigger animals, namely humans.)

Perhaps it was these recent tragedies which caused The Optimistic Child to jump out at me from a friend's bookshelf. Written by Martin E. P. Seligman, with his assistant researchers, Karen Reivich, Lisa Jaycox, and Jane Gillham, and published by Houghton Mifflin Company in 1995, it is subtitled A Revolutionary Program That Safeguards Children Against Depression & Builds Lifelong Resilience.

It is a most intriguing book and would be worth reading by every parent and educator working with young children, because they have devised techniques to help children build their own immunization to pessimistic feelings and thoughts. It is these feelings that lead to the high level of depression that exists in the youth of America, which he notes affects a quarter of all children today. Many move on to attempt suicide.

The Optimistic Child describes how the "self-esteem" movement has been less than uplifting to America's children. Seligman points out that all the self-affirmations in the world have a difficult, if not impossible, time actually defeating sad and pessimistic feelings. In fact, it is his firm belief, based upon their observations in classrooms, that

By emphasizing how a child feels, at the expense of what the child does - mastery, persistence, overcoming frustration and boredom, and meeting challenge - parents and teachers are making this generation of children more vulnerable to depression.

In contrast to the literature about self-esteem, which promotes the idea that low self-esteem causes all the woes of the children, Seligman points out that self-esteem is the by-product of doing things well, of being successful at a task, of creating something that a child feels is good (not something about which adults mouth false adulation). How many times have you heard someone tell their child, who did not do something successfully, that they did fine...they were great. You know that the child does not believe that, and if the parent is actually not being truthful, what is the lesson being learned by the child? Not only was there no positive outcome, but Mom or Dad even lie about it.

The authors' research has found that deeply held optimistic/pessimistic patterns get set early in a child's life. Through studies in classrooms, they devised methods to change global patterns of self-blame to specific, behavioral self-blame. An example: "I got a D on that test because I'm stupid" (pessimistic: permanent, pervasive, and internal) to "I got a D on that test because I didn't study hard enough" (optimistic: temporary, specific, and internal).

They emphasize that criticism of a child's actions must be accurate (not exaggerated but not omitted, either), and done with optimistic explanations pointing out specific causes of the problem. And equally as important is what adults say when they criticize themselves or other adults and their children hear them. Keywords to leave out of any criticism (and boy, does this hold true no matter what age!) are "ever" and "always."

The book contains questionnaires to determine the level of a child's optimism and rate a child's depression and how to assess the responses. There are many examples of adult-child interactions from their classroom work in the Penn Prevention Program, which they devised and operated for several years in schools around Philadelphia as part of their research. It describes how parents can lay the foundations for life-long optimism in their children and actually "immunize" their children against depression and pessimism, to "unlearn" helplessness. Many exercises are included which implement doing so.

When it comes to preschool children who don't have the skills to recognize their thoughts and then devise ways to dispute them, there are three principles essential for an optimistic child: "mastery, positivity, and explanatory style." Mastery (or control) is when a child learns that an action creates an effect: pushing on a button makes a doll talk. If the doll doesn't talk each time the button is pushed or talks without having the button pushed, then the child loses interest. When there is no way to consistently connect an action with an effect, a sense of helplessness can overtake the child and passivity results.

Positivity is honest praise for a child's successes and not just to make him or her feel better. The level of praise fits the accomplishment and failure is not praised; it is honestly assessed in relation to the skill level of the child. Positivity will warn a child that continued poor behaviors will result in appropriate punishment and also warn a child when something hurtful is going to happen, such as a shot at the doctor's office. With consistent warnings, a child learns that when they are absent, he or she needn't be afraid of losing privileges or be taken by surprise by the pain of a doctor's needle.

Explanatory style comes directly from the parents' mouths since young children mimic so well. This is where it's important for the adults to understand and listen to their own methods of explaining how things are good or bad in their lives and to assess their behaviors, not their personalities.

Seligman believes that the benefits of optimism are clear:

It will help him fight depression when the inevitable setbacks and tragedies of life befall him. It will help [her] achieve more - on the playing field, in school, and later at work - than others expect of [her]. And optimism carries better physical health with it - a perkier immune system, fewer infectious illnesses, fewer visits to the doctor, lower cardiac risk, and perhaps even a longer life.

What I liked about The Optimistic Child, however, is that Seligman is not a gushing proponent of unbridled optimism. He points out, towards the end, that one thing pessimists have going for them is they see reality more clearly than optimists. What he hopes this book will teach is the effective teaching of children to be accurate optimists, to take realistic views of themselves and of the world around them:

Optimism is not chanting happy thoughts to yourself...is not blaming others when things go wrong...not the denial or avoidance of sadness or anger....When you teach your child optimism, you are teaching him to know himself, to be curious about his theory of himself and of the world. You are teaching him to take an active stance in his world and to shape his own life, rather than be a passive recipient of what happens his way. Whereas in the past, he may have accepted his most dire beliefs and interpretations as unquestionable fact, now he is able to reflect thoughtfully on these beliefs and evaluate their accuracy. He is equipped to persevere in the face of adversity and to struggle to overcome his problems.

But he warns:

Optimism, then, is not a cure-all. It will not substitute for good parenting. It will not substitute for a child's developing strong moral values. It will not substitute for ambition and a sense of justice. Optimism is just a tool, but a powerful tool. In the presence of strong values and of ambition, it is the tool that makes both individual accomplishment and social justice possible.

There is much useful knowledge, and many skills taught, in this book. Seligman and his assistants spent much time devising and implementing their research and their testing programs. What they've put forth could be of valuable assistance to families living with a child who is following a negative path. While it sometimes grated a bit to find myself fitting into the "baby boomer teaching my child to feel good group," the more I thought about my own children, the more I could see how their lives might have been happier in adolescence if these skills had been widely taught.

The odd thing is, I believe that my underlying credo is one of accurate optimism. I haven't figured out how that came to be, given my experiences, but I'm grateful for it.

May truth blossom from your hearts,

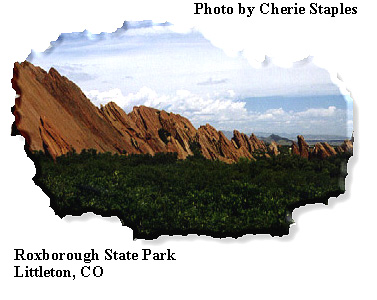

Cherie Staples

Skyearth1@aol.com