I recently walked a new design of a labyrinth. Pamela Ramadai wrote about walking labyrinths in June 1998's Seeker. We see each other from time to time, particularly as she takes her business of Labyrinths Goods on the metaphysical show route and lays out portable labyrinths to walk on. These have been seven-ring labyrinths painted on heavy, rip-stop nylon with images of rocks and other earth creatures incorporated into the artwork.

In May she showed me a new design of a "personal" labyrinth which she had just received from a woman who lives in the northern mid-west, I believe, one that is a little smaller than the traditional seven-ring. In about a month, she had gotten it painted onto nylon and brought it with two seven-rings and the Unity Church's big 11-ring canvas to a "new age" trade show in Denver. Laid out in a spacious meeting room above the marketing floor, they provided a quiet respite.

The new labyrinth was front and center when I walked in. I believe the nylon background was a dark green. The portal was outlined on one side by a tree trunk whose sweep toward the center radiated into rings of luminous green and whose roots embraced large rocks, The outer-most circle was a rainbow.

As I stepped "into" it and along it, tears were filling my eyes, the first time ever that I've been strongly affected in a labyrinth. The center turned so tightly that I felt I was spinning, and then unspinning when I came back out. As I walked it, Mollie Beattie came to mind.

So, who is Mollie Beattie and what does she mean to me?

I first met her when she was on the board of directors of the non-profit I worked for in the early '80s in Vermont. She was a forester and worked for a foundation that owned quite a bit of timberland. She was the first woman appointed Commissioner of Vermont's Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation, a big taste of stepping into the old boys' network of governmental forest politics. It's doubtful that it was her first taste because, for any woman, becoming a forester in the '60s and '70s meant she had to buck the male bastion of forestry.

She was inordinately skilled in resolving conflicts---a clear-headed person who seemed to have worked through, or simply not had, many of the usual ego issues. She took that clarity and honesty to Washington, DC, when she was appointed the Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1993 by the newly-elected president. There, she experienced the fires of the super-entrenched, old-boy politics and government networks in the wildlife world. But she always garnered respect, it seems, no matter how far apart she and her adversaries were on issues.

I didn't know her well, but whenever she was in Montpelier and stopped by the office of the organization that I worked for, she always evinced interest in whatever I was doing. It was as if she had never left Vermont's woodlands.

The news from DC in the late summer of '95 that she had a brain tumor and surgery to remove it was shocking. There was some hope that winter that she would beat it. That didn't happen. By May, I believe, she was back home, returning to Vermont to die in Grace Cottage Hospital in Townshend, with a courage and acceptance that warmed everyone who touched her in any way.

She died on June 27, 1996. She had lived 49 years. I cried, the first time ever at someone's death. I've found that whenever I've thought of her, talked about her, during these three years, I cry. It was June 26, 1999, when I walked the new "tree" labyrinth and, with the tears welling, thought of Mollie Beattie. The desire to write her biography resurfaced, an idea that had sprung to life soon after her dying, a desire that I have no experience fulfilling, since I've not written anything longer than these essays. Nor have I done any research of the nature that gathering materials for a biography would entail. But it pulls me.

I have not understood what the connection is between us. Why thinking of her causes me to cry and feel inordinately sad. But it is obvious that Mollie Beattie means something of import to me. I am waiting to discover just what it is.

Shortly before she died, I wrote a poem and sent it to her. Don't know if she was able to read it or hear it, but whenever I'm leafing through my poems, I stop and reread it. I'll share it with you.

WHERE SHALL I GO FOR COMFORT?

I shall go to the forest,

and the spirit of the trees

shall breathe peace into my being.

I shall go to the wild ones,

and the great bear and the firefly

shall guide my path.

I shall turn my face to the great sky,

hold my arms open to the four winds,

and their spirits shall sweep remorse from my soul

and I shall be healed forever.

---------- June 1996 for Mollie Beattie

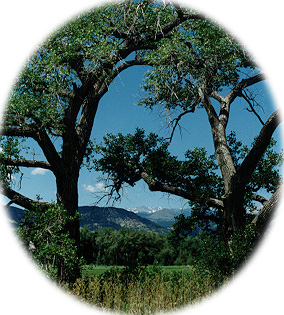

The photograph above was taken on 55th Street in Boulder, CO. I discovered this road one day and was amazed to feel that I was out in the country, wandering along a cottonwood-lined creek, with a hayfield on the other side and a backdrop of the Flatirons peaks and the further range of high peaks. It didn't feel like I was practically within hailing distance of a large city, but I was. I would say it proves the unqualified success of Boulder's (city and county) efforts of buying and protecting open space.

Table of Contents

Letter to the Author: