Seeker Magazine - September 2004

Draining the Champagne Glass

by Peter Sawtell

Return to the Table

of Contents

As the US slogs through its long election season, politicians spell out their positions on lots of issues -- health care, the economy, national security, personal and social morality, and the environment. When I hear those policy statement, I'm almost always aware that the candidates just don't get what "the environment" is all about.

It is not that the politicians are any different than other folk. It is just that the dynamics of a political campaign force them to speak up with explicit policy statements.

Usually, the candidates discuss "the environment" in terms of specific issues -- clean air, toxic waste, or forest management. That compartmentalized approach, though, serves us all badly. When we don't see how the realities of our global ecology touch on every other issue and concern, then we're led into dysfunctional ways of living in the world.

Such a comprehensive view is a hard notion to absorb in the abstract. It starts to make sense when we work through a couple of specific steps in building a different awareness.

As part of a seminar that I helped lead recently, I spent two hours guiding the participants through a series of exercises with that goal. We came to a vivid awareness of how a core ecological principle reshapes the way we deal with questions of economic justice.

+ + + + +

I started by having all the seminar members calculate their "ecological footprint" -- a quick multiple-choice quiz that tells you how much of the Earth's resources are consumed by your lifestyle. (See www.MyFootprint.org ) The results are presented in vivid terms: "if everyone lived like you, we would need __ planets." The scoring also rates the individual's resource use in comparison with an "average American."

If everyone on Earth lived like I do, it would take about 3 planets to supply all of our needs. My lifestyle is relatively frugal by US standards. The average American uses about twice as many resources as I do.

The members of our class had "footprints" in the range of 2 - 10 planets. As we processed those figures, we were all caught by the gut-level realization that our travel, housing, food and other purchases are not sustainable. Even for the most moderate of us, our lifestyle demands more than the Earth can provide.

Obviously, we don't live in a world where "everyone lives like you." People in the US consume far more resources than the global average. (Even so, worldwide, humans are now consuming 1.2 times what the Earth can provide.)

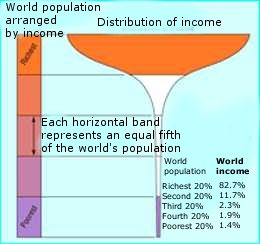

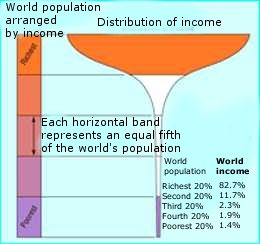

So, we also looked at a chart of disparities in resource use around the world. A United Nations report a few years ago included a diagram that has come to be known as "the champagne glass" of global income. That graph dramatically illustrates that uneven distribution of wealth. (The image is on our website: www.eco-justice.org/E-040827.asp)

So, we also looked at a chart of disparities in resource use around the world. A United Nations report a few years ago included a diagram that has come to be known as "the champagne glass" of global income. That graph dramatically illustrates that uneven distribution of wealth. (The image is on our website: www.eco-justice.org/E-040827.asp)

The UN statistics clump income data within "quintiles" of the world population. The poorest fifth -- the very narrow "stem" of the "champagne glass" -- receives only 1.4% of the world's income. The flared out top of the glass, representing the richest fifth, receives 82.7% of total world income.

The champagne glass, like the ecological footprint, generates a powerful gut reaction. "It isn't fair that so many should be poor and so few consume such a large proportion of the world's resorces." But how do we solve that problem?

Most good, compassionate, liberal folk -- at the seminar, and elsewhere --want to deliver the poor from their poverty. Indeed, that is the espoused goal of the neo-liberal economic policies which underlie current trends in economic globalization, and that are affirmed by so many political candidates. Economic growth will make us all richer.

The ecological footprint, though, tells us that we can't smooth out the world's inequalities by making the poor much richer. Because if everybody lived like the average American -- like us folk in that top quintile -- it really would take 6 planets to meet all our needs.

The point becomes clear. When we bear in mind an environmental awareness about the limits of our world, it profoundly changes the way we think about economic justice.

In a limited world, we can only achieve a more even distribution of resources if the wealthy stop consuming so much. In a limited world, we, the wealthy, must be seen as the problem, not the ideal. That is a direct challenge to most economic policies.

+ + + + +

If "the environment" is just about clean air or endangered species, then we can keep it pretty well separated from the other concerns in our lives. Saving the whales or reducing mercury emissions from power plants doesn't change our perspectives about global poverty or our theories of economic development.

A broader sense of "the environment" leads us to an awareness of the inter-relatedness of all things on a limited Earth. Thinking about "the environmental" in that way requires a different approach to all of the issues that this year's candidates are discussing -- the economy, health care, national security, and on through the list.

In this election season -- as we take part in conversations about platforms and policies, and as we make our choices about how to vote -- may we all see how the central environmental fact of an overtaxed world redefines all matters of public policy.

(Copyright 2004 by

Peter Sawtell -

Reproduction is permitted provided that you include acknowledgement of

the author and a link to Eco-Justice Ministries.)

Table of

Contents

Letter to the Author: Peter Sawtell at ministry@eco-justice.org

So, we also looked at a chart of disparities in resource use around the world. A United Nations report a few years ago included a diagram that has come to be known as "the champagne glass" of global income. That graph dramatically illustrates that uneven distribution of wealth. (The image is on our website: www.eco-justice.org/E-040827.asp)

So, we also looked at a chart of disparities in resource use around the world. A United Nations report a few years ago included a diagram that has come to be known as "the champagne glass" of global income. That graph dramatically illustrates that uneven distribution of wealth. (The image is on our website: www.eco-justice.org/E-040827.asp)