Winter Solstice, 1992 my first day on the job at The Wilderness Society, and Pat, one of my new colleagues, takes me around to meet the handful of staff actually working four days before Christmas. One of these was, of course, our counselor, Senator Gaylord Nelson, Founder of Earth Day, hero of the environmental community, a man who was in the Senate when I was in diapers. I was a bit intimidated. We step into the Senator's office for an introduction that goes like this:

Pat: "Gaylord, I'd like you to meet our new economist Spen "

The Senator (interrupting): "What the hell do we need another economist for? Aren't they the kind who lie awake at night wondering whether what happens in the real world could work in theory? I heard that an economist is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing!"

Fortunately, he was half kidding, and fortunately, we share an admiration for at least a few economists, including Herman Daly.

Nevertheless, economists do deserve a good deal of the ribbing we get. Our theory of value, for example, comes from John Locke who considered the wilderness a wasteland until man joins his labor to it. The blank spaces on the map, in his view, had no value until we extracted their resources and turned them into something really useful. Locke was, if you'll forgive the seeming double negative, a man who did not know the value of nothing.

Nowadays, many environmental economists are building their careers by trying to estimate, to 3 significant digits, the monetary value of this or that feature of the natural world. By the logic of cost benefit analysis, we can then determine whether the feature is worth protecting from man's next endeavor to join his labor to the untrammeled gifts of nature.

I am afraid that I don't see much hope for a civilization so stupid that it demands a quantitative estimate of the value of its own umbilical cord. David EhrenfeldGiven my introduction to working for The Wilderness Society, and a healthy skepticism regarding my own discipline, I hope you don't mind my taking a little license with my assigned topic. You have not asked, after all, for a presentation on the price of wilderness. Instead, our topic is the value of wilderness, and I appreciate the chance to speak to an understanding that transcends dollars and cents.

If you want dollars and cents, please pick up a copy of The Wilderness Society's recent study by Loomis and Richardson. In it, you'll learn that proximity to wilderness adds about 13 percent to the price of residential parcels around the Green Mountain National Forest, and that recreational use of 555 acres of eastern wilderness supports one job in the local economy. The report is an excellent summary of what we know about the monetary value of wilderness, and it provides much richer detail than I can provide tonight.

I cannot completely shed my economist's skin, however, and I do think there is something to gain from the fundamental concern and concept of my discipline. Those are the behavior of people when confronted with choices, and the notion of opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is the value of what is not done when a choice is made. The opportunity cost of a chosen action or condition is the value of whatever action or condition is forgone in making the choice.

In the special case of competitive markets (which may exist only in theory), we might say that the prices we observe approximate the true opportunity cost of the good or service purchased. More realistically, we may recognize that markets are not competitive, and that they do not reflect the value of all relevant alternative actions and conditions.

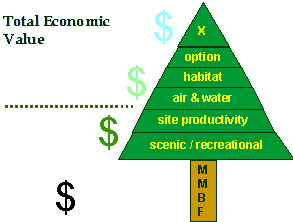

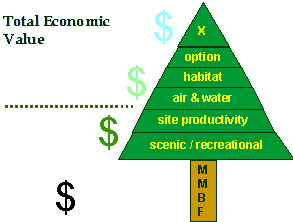

What's missing in market prices is captured by the concept of "total economic value". Consider this illustration of the value of a forest. What is immediately apparent and readily quantifiable as a price is the value of timber that can be harvested from the forest. Lots of people buy and sell timber, and we can assume that the current value to society of the services provided by a unit of cellulose is approximately equal to stumpage price.

But there is much more to a forest than meets the eye of the market. There are scenic and recreational opportunities that may or may not be reflected in travel and tourism, sporting goods and other markets. There is also site productivity, which due to discounting a reflection of our natural preference for consumption today over consumption tomorrow is probably only weakly represented in formal markets for forestland.

Next there is air and water quality and wildlife habitat. Cleaner water from Green Mountain National Forest wilderness (and the Batelle Lands), for example, may help make Otter Creek Stovepipe Porter both cheaper to produce and a better product. That gift of nature is an essential asset that Otter Creek Brewing's accountants may not be able to fully reflect on the balance sheet and for which we consumers don't fully pay for at the local pub. (Though, in my opinion, it would be a bargain at any price.)

Further development of market-enhancing and market-like institutions, such as forest products certification and tradable carbon sequestration credits, will provide a monetary return for stewardship of these values and make their opportunity costs more "real."

Finally, there are so-called "option" and "existence" values. These are what people would theoretically pay to preserve the option of future use of the forest, to pass the forest on unimpaired to future generations, and for the simple knowledge that the forest and all its resources exist, even though the person who holds that knowledge has no expectation of ever setting foot in the forest.

The monetary value of each of these different classes of forest resources may be of comparable size the dollars are not all in the cellulose. Indeed, Robert Costanza and his co-authors of the famous Nature study estimate that only about 10 percent of the value of temperate and boreal forests has anything to do with commodity production. Less than a third has to do with direct use of forest resources. (This would be the portion below the dotted line in my diagram).

Here are bits of eternity, which have preciousness beyond all accounting. Harvey BroomeHowever, the farther one gets away from the resources for which organized markets exist, the harder it is to see those monetary values and, therefore, the easier it is for public and private decisions to ignore them. We under-count the opportunity costs and, consequently, we over-use those natural assets that do have discernable prices.

But even if we could account for all of the individual "bits of eternity," there are still the implications of broad choices we may face concerning wilderness and nature in general. So I would like to turn to what some have suggested we might be willing to give up to have wilderness and, conversely, what might be lost with the loss of wilderness. I hope you will forgive my musings on what monetary value might be associated with some of those macro-level opportunity costs. It is an occupational hazard.

I hope you will also forgive the over-representation of Wilderness Society founders, Aldo Leopold especially, in these thoughts. The tendency to "quote the founder" is a particular rhetorical tic instilled in Virginia graduates, as it seems that one could letter there in quoting Mr. Jefferson.

The opportunity to see geese is more important than television . . . Aldo LeopoldTo Leopold, geese were one of the "wild things" without which some people cannot live. They come from and go to places unknown, and the chance to see them means the existence and integrity of those places. One of the reasons I love this time of year is that on days when the flocks pass overhead I can tell my daughters that we don't need to watch TV, because we've already had something much more important. (The real beauty is that they often agree.)

How much more important can be answered, in part, by opportunity cost. Taking Leopold at his word (which I do remember he's a Founder), we might peg the value of the opportunity to see geese at the contribution of television to the U.S. economy. That figure may be as high as $80 billion, if you count basic cable, broadcast TV, pay-per-view and video rentals.

$80 billion! For a suburban pest! And that for the mere chance of seeing them. Never mind the chance to study, photograph or otherwise enjoy them.

What then would be the value of the opportunity to hear wolves? Or to track lynx? Or to be tracked by catamounts? Those values have got to be greater than, say, the Disney channel, or cell phones or (just maybe) Napster.

. . and the chance to find a pasque flower is a right as inalienable as free speech. Aldo LeopoldNext, Leopold compares the chance to connect with another wild thing to an even more fundamental feature of our culture.

Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map? Aldo LeopoldElsewhere, he goes that comparison 40 times better in describing the opportunity cost of perhaps the signal characteristic of the ever shrinking wilderness.

I don't know what we spend defending the right to free speech specifically, but if we take the contribution of the legal profession to Gross Domestic Product as an indicator of the cost of defending all of our freedoms, it is a little over $100 billion dollars per year. According to Leopold's logic, we might expect to pay that amount simply to maintain the opportunity to get lost in unknown territory.

Think about it. If we can afford $100 billion a year for lawyers, is one billion a year for the Land and Water Conservation Fund too much to ask?

I am glad that I shall never be young without wild country to be young in. Aldo LeopoldLeopold also suggests that the loss of wild country is as profound, irreversible, and lamentable as the loss of youth. And (by now you know what's coming) we American's spend an awful lot of money trying to extend or regain our lost youth. We drop $4.4 billion at retail cosmetics shops alone, plus another $10.1 billion at health and fitness centers and who knows how much for Rogaine and Viagra.

According to Aldo Leopold, take television and youth here, forty freedoms there, and pretty soon you're talking serious money.

The surest way into the universe is through a forested wilderness. John MuirThis isn't quite equal time for the Sierra Club's founder, but in terms of scale, John Muir's expression of the opportunity cost of wilderness clearly surpasses Leopold's.

A way into the universe surely means many things to many people. Taken together the treasure we've spent in our various and often vain attempts to get connected to the universe must be immense. But, Muir suggests, wilderness is worth much more, because the way is sure.

In fact, according to John Hendee and his co-authors at the University of Idaho, wilderness therapy using wilderness experiences to treat drug addiction, criminal behavior and other means by which people have lost their way into the universe is now an industry pumping some $143 billion dollars per year into the U.S. economy.

I promise that's my last dollar-valued expression of the opportunity cost of wilderness, but I would expect it to be just the tip of the iceberg. Many, many more people use wilderness and other experiences in nature to gain perspective, relax, restore the spirit, and build self-esteem through physical and mental challenge. And we do so long before loss of perspective, stress, or dip in spirit and sense of self reaches a clinical stage. We would have to count the cost of medication, therapy and other treatments not needed among the opportunity cost that is, the economic value of this aspect of wilderness.

Speaking of "the way" . . .

What will a man be profited, if he gains the whole world, and forfeits his soul? Jesus Christ (Matthew 16:26)Many in the conservation community are rediscovering the spiritual value and benefits of wilderness. I personally have found these the greatest and most profound. Indeed I would likely be somewhere quite different tonight were it not for a trip in 1983 in what is now the Lewis Fork wilderness of the Jefferson National Forest. That trip encouraged me to abandon some ineffective "ways into the universe" (call it repentance if you like) and exposed me to untrammeled creation, our truest remaining expression of a living and loving God.

Translated into the language of economics, and viewed through the lens of my own experience, Jesus' cost/benefit analysis suggests that it would be "sub-optimal" to trade, even for the whole world, the places and experiences that are so effective in the process of redemption.

I am not suggesting that wilderness is the only factor or even that it is absolutely necessary. The Lord does work in mysterious ways. But there is ample evidence that He works particularly well in wilderness.

. . . confess over [the goat] all the iniquities of the sons of Israel . . . And lay them on the head of the goat and send it away into the wilderness. Leviticus 16:21Yom Kippur, the annual Day of Atonement, is coming up. Originally, a goat would be led off into the wilderness on that day, carrying the collective sin of the nation on its head. Thanks to the scapegoat and the wilderness, Israel could then start the new year with a clean slate.

In those days John the Baptist came, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, saying, "repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand." Matthew 3:1-2Jumping back to the New Testament, consider John the Baptist the one "crying in the wilderness, 'prepare the way of the Lord.'"

What strikes me as significant is that John did not call people to the temple, nor to the palace, and certainly not to the marketplace to get in touch with their spiritual need. Rather, his call to repentance came from the wilderness, a place where social status does not count, the cares of daily life do not distract, and the comforts of home do not dull us to what God might have to say.

I must digress for a moment here, because there are some who claim that wilderness protection is tantamount to state establishment of an "environmental religion." (A lawsuit alleging as much has recently been thrown (laughed?) out of court in Michigan.) That is not what I am talking about, however.

Wilderness is not, and cannot contain, God even Jesus said we should not be fooled into going to look for Him there (Matthew 24:26). Rather, as Jonathan Edwards notes, unspoiled nature is a vestige of the glory of original creation and an "image or shadow" of the Creator Himself.

Not for television.

Not for forty freedoms.

Not for the whole world.

What's the price of wilderness? We economists can estimate a portion.

But the true and total value? That's either "beyond all accounting," as Harvey Broome said. Or, giving Senator Nelson the last word, it is the whole of what we could count. He writes:

The wealth of the nation is its air, water, soil, forests, minerals, rivers, lakes, oceans, scenic beauty, wildlife habitats and biodiversity . In short, that's all there is. That's the whole economy.