When I received this summer's issue of Orion Magazine (a wonderful compilation of environmental and natural world writings) and read an excerpt of Sandra Steingraber's Living Downstream: An Ecologist Looks at Cancer and the Environment, I knew I had to read the whole book. After reading the book, I knew it was going to be next in "Skyearth Letters."

It is an important, even critical, book. Sandra Steingraber picks up Carson's theme after some thirty years with thousands more chemicals compounds having been devised, generated and put into the environment. Her advantage is having access to larger sources of data (thanks to the hard work of the environmental movement which fought for the Disclosure of Information Act and other legislation that requires environmental safeguards of varying degrees).

Steingraber speaks as a cancer survivor, having gone through treatment for bladder cancer when she was in college, as a biologist (doctorate), as someone who watched a friend die from a rare form of cancer, and as someone who grew up in the toxic stewpot of central Illinois. If it is hard to consider Illinois as filled with toxic wastes, just read her description of the immediate area that she grew up in:

Normandale is situated on a triangular wedge of land near Dead Lake, a dumping pond for industrial wastes near the [Illinois] river's east bank. It is flanked on two sides by industry: a foundry, a grain-processing plant, a couple of chemical companies, a coal-burning power plant, and an ethanol distillery. Its third side is bounded by a landfill that operated without state permits until the Illinois Pollution Control Board shut it down in 1988.That description, of course, does not include the pollution from agricultural run-off from the great corn and soybean fields draining into the tributaries of the current Illinois River and seeping into the ground water and now-buried river channels of the Mahomet and ancient Mississippi Rivers. Steingraber returns to the Illinois landscape because, she says, it is so typical. It is also where her mother's family still farms:

...it is important to me to maintain a relationship with both Illinoises--the present and familiar one as well as the Illinois that has vanished and is barely discernible. What remains of the twenty-two million acres of tallgrass prairie that once covered this state is the deep black dirt that those grasses produced from layers of sterile rock, clay, and silt dumped here by wind and glaciers. The molecules of earth contained in each plowed clod are the same molecules that once formed the roots and runners of countless species unfamiliar to me now.She continues, though, in a darker vein about the Illinois of today:

To the 89 percent of Illinois that is farmland, an estimated 54 million pounds of synthetic pesticides are applied each year....In 1950, less than 10 percent of cornfields were sprayed with pesticides. In 1993, 99 percent were chemically treated....In 1993, 91 percent of Illinois's rivers and streams showed pesticide contamination....A recent pilot study found that one-quarter of private wells tested in central Illinois contained agricultural chemicals....[E]ach year, Illinois injects some 250 million gallons of industrial wastes--which, until recently, included pesticides--through five deep wells that penetrate into bedrock caverns....Illinois exports hazardous wastes but also imports it--almost 400,000 tons in 1992--from almost every state except Hawaii and Nevada. In this same year, Illinois industries legally released more than 100 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the environment.As a child of the chemical age, as all baby boomers are, she notes that she shares a birth year with atrazine and the peak use of DDT and a decade of the huge manufacturing of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls). Both DDT and PCBs have been banned as proven to cause cancer. Atrazine (look on the label of "Round-up" in your local store) is a member of the triazine herbicides which stop photosynthesis. Applied directly to the soil and water soluble, these compounds now are present in "groundwater, as well as about 98 percent of midwestern surface waters" where they poison algae, plankton, and aquatic plants that are the basis of the freshwater food chain. They've also been detected in raindrops from the midwest to the northeast.

Triazine herbicides are known to cause cancers in rats and hamsters; what is not known is how much it takes to cause cancers in humans. She notes that case control studies in Italy show "a correlation between exposure to triazine herbicides and ovarian cancer among women farmers." She goes on to say:

We are exposed to these herbicides not only through consumption of produce--oranges and apples appear to be major sources of dietary exposure to simazine, for example--but also through meat, milk, poultry, and eggs, resulting from the ubiquitous use of corn in animal feed. Crop plants that are tolerant of triazines, such as corn, will metabolize the herbicide molecules--as will the animals who feed on these crops--but it is not at all clear how complete this process is nor how carcinogenic the metabolites themselves might be. The EPA's [Environmental Protection Agency] description of what is known about the movement of triazines through the human food chain is full of qualifiers, disclaimers, and expressions of frustration....[M]ore than three decades after the introduction of chloroplast-destroying chemicals into American agriculture, the cancer risks we have assumed from eating food grown in fields sprayed with them--and from drinking water that has percolated through these fields--have yet to be determined.Why should we be concerned? Steingraber's focus on cancer comes from the personal, to be true, but it also comes from alarming statistics, ones that we know in our gut to be true from our own experiences. She states that the incidence of all types of cancer in the U.S. has risen nearly 50 percent between 1951 and 1990. When lung cancers are not included (due to personal lifestyles of smoking), the rate rose 35 percent. It's the leading cause of death among people aged thirty-five to sixty-four.

[C]ancers that show both increasing incidence and increasing mortality: cancers of the brain, liver, breast, kidney, prostate, esophagus, skin (melanoma), bone marrow (multiple myeloma), and lymph (non-Hodgkin's lymphoma) have all escalated over the past twenty years and show long-term increases that can be traced back at least forty years.She goes on to quote two senior scientists at the National Cancer Institute who said, thirty years ago, "Cancers of all types and all causes display even under already existing conditions, all the characteristics of an epidemic in slow motion." The scientists further stated that it was being fueled by "increasing contamination of the human environment with chemical and physical carcinogens and with chemicals supporting and potentiating their actions."

A scientist who has spent field time gathering test data herself, Steingraber takes myriad reports and clearly ties results into a coherent text describing the rise of cancers and the rise of toxic chemicals. Her description of how the ozone of the upper atmosphere is broken down by CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) therefore allowing more ultraviolet rays to reach earth and cause melanomas, would, I think, be undestandable even to those with only a smattering of scientific knowledge. She describes chemical and biological actions with images that are easy to follow. She writes lyrically, poetically, and scientifically, but there are no formulas and tables that cause one's mind to drift away from the subject.

I haven't touched upon;

There was so much that I wanted to include that it was hard to make choices. I told a good friend, who lives an ecologically responsible life as best as possible, that this was an excellent book to read. Her response was that she simply couldn't bear to read about all the toxins in our lives. I have to agree that reading it made me want to retreat to somewhere clean, but--Steingraber makes this point a number of times--there is no such place on this planet. Not any more. Not with dieldrin in the arctic ice.

I encourage you to read the whole book if you have the slightest interest in what has been and is part of our everyday environment and their effects upon your body. And I hope that there are more people who want to know the specifics, so that then they can more effectively work toward creating a worldwide healthy environment. We cannot leave it to the politicians and the toxicologists and the chemists to create one for us.

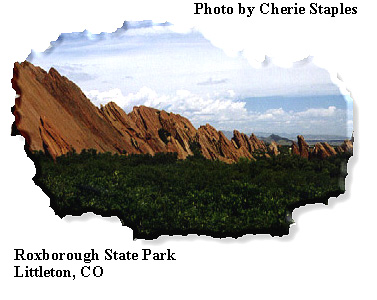

Cherie Staples